Search | Sitemap | Navigation |  |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| Jenny Povey |

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900)

Friedrich Nietzsche, 1844-1900. (http://files.db3nf.com/pictures/authors/nietzsche.jpg, March 26, 2004)

"[I]n my thirty-sixth year of life I arrived at the lowest point of my vitality - I still lived, but without being able to see three paces in front of me. At that time - it was 1879 - I resigned my professorship at Basel, lived through the summer like a shadow in St. Moritz and the following winter, the most sunless of my life, as a shadow in Naumburg. This was my minimum: meanwhile, 'The Wanderer and His Shadow' came into existence. Doubtless, I knew about shadows in those days ... In the following winter, my first winter in Genoa, that sweetening and spiritualization which is almost inseparable from an extreme poverty of blood and muscle, brought forth 'The Dawn.' The perfect brightness and cheerfulness, even exuberance of spirit, that is reflected in the said work, is in my case compatible not only with the most profound physiological weakness, but also with an excess of pain. In the midst of the torments brought on by an uninterrupted three-day headache accompanied by the laborious vomiting of phlegm, - I possessed a dialectician's clarity par excellence, and in utter cold blood I then thought out things, for which when I am in better health I am not enough of a climber, not refined, not cold enough."

(Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo - How one becomes what one is, Why I am So Wise, 1888, http://www.geocities.com/thenietzschechannel/eh3.htm, March 26, 2004)

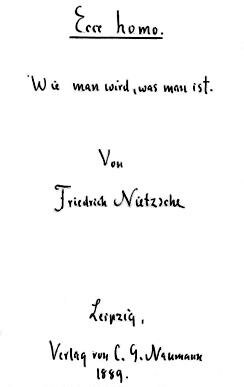

Nietzsche's sketch for the title page of Ecce Homo. Wie man wird, was man ist. (http://www.dartmouth.edu/~fnchron/files/images/eh.gif, March 26, 2004)

"Has anyone at the end of the nineteenth century a clear idea of what poets of strong ages have called inspiration? If not, I will describe it. - If one had the slightest residue of superstition left in one's system, one could hardly reject altogether the idea that one is merely incarnation, merely mouthpiece, merely a medium of overpowering forces. The concept of revelation, in the sense that suddenly, with indescribable certainty and subtlety, something becomes visible, audible, something that shakes one to the last depths and throws one down, that merely describes the facts. One hears, one does not seek; one accepts, one does not ask who gives; like lightning, a thought flashes up, with necessity, without hesitation regarding its form, - I never had any choice. A rapture whose tremendous tension occasionally discharges itself in a flood of tears, now the pace quickens involuntarily, now it becomes slow; one is altogether beside oneself, with the distinct consciousness of subtle shudders and of one's skin creeping down to one's toes; a depth of happiness in which even what is most painful and gloomy does not seem something opposite but rather conditioned, provoked, a necessary color in such a superabundance of light; an instinct for rhythmic relationships that arches over wide spaces of forms - length, the need for a rhythm with wide arches, is almost the measure of the force of inspiration, a kind of compensation for its pressure and tension ... Everything happens involuntarily in the highest degree but as in a gale of a feeling of freedom, of absoluteness, of power, of divinity ... The involuntariness of image and metaphor is strangest of all; one no longer has any notion of what is an image or a metaphor, everything offers itself as the nearest, most obvious, simplest expression. It actually seems, to allude to something Zarathustra says, as if the things themselves approached and offered themselves as metaphors (- 'Here all things come caressingly to your discourse and flatter you: for they want to ride on your back. On every metaphor you ride to every truth. Here the words and word-shrines of all being open up before you; here all being wishes to become word, all becoming wishes to learn from you how to speak -'). This is my experience of inspiration; I do not doubt that one has to go back thousands of years in order to find anyone who could say to me, 'it is mine as well.'"

(Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo - How one becomes what one is, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, 1888, http://www.geocities.com/thenietzschechannel/eh11.htm, March 26, 2004)

References

Anonymous. The lonely Nietzsche and his migraine. Minn Med 1970; 53: 726.

Möbius PJ. Über das Pathologische bei Nietzsche. Grenzfragen des Nerven- und Seelenlebens: Einzeldarstellungen für Gebildete aller Stände. Heft 17. J.F. Bergmann, Wiesbaden 1902. 2. Aufl. Barth, Leipzig 1904.

Nicola U, Podoll K. L'enigma di Giorgio de Chirico. La nascita della pittura metafisica dallo spirito dell'emicrania. Confinia Cephalalgica 2002; 11: 9-24.

Nicola U, Podoll K. L'aura di Giorgio de Chirico. Arte emicranica e pittura metafisica. Mimesis, Milan 2003.

Yalom I. When Nietzsche Wept. Harper Perennial, New York 1993. (See here)

Author: Klaus Podoll

Last modification of this page: Wed. July 14, 2004

| Jenny Povey |

Top of the page

Top of the page| · | News |

| · | Medical Professionals |

| · | Medical Studies |

| · | Giorgio de Chirico |

| · | Marvin Minsky |

Copyright © 2005 Migraine Aura Foundation, All rights reserved. Last modification of this site: August 25, 2006

Thanks to: RAFFELT MEDIENDESIGN and GNU software | webmaster@migraine-aura.org

http://migraine-aura.org/EN/Friedrich_Nietzsche.html